University of Adelaide Law School

8 September 2023

May I begin by acknowledging the Kaurna people and pay my respects to elders past, present and emerging.

Participating in Democracy

It is wonderful to be here at the University of Adelaide Law School and to be here during the University’s 140th anniversary.

It is a university that has added so much to our Australian story – from Howard Florey and Douglas Mawson to Dame Roma Mitchell and Governor Frances Adamson. And in politics, personalities as different as Christopher Pyne and Julia Gillard.

This university profoundly matters in our national life.

In this campaign I’ve made a deliberate point of talking at universities and to students.

I’ve spoken at the University of Canberra, who have a tremendous program of University outreach, and at Griffith University’s Law School, who are running a specific class about the people and the Constitution.

I want to encourage the students here and listening on the livestream not only to think about their vote on 14 October, but to think about participating as well.

You see, the law – which you study here – is very much the anatomy of our democracy.

And it’s the involvement of citizens which is the beating heart of democracy.

You are not too young to have a say and not too young to participate.

In 1998, at the age of 21, I was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention – and was subsequently appointed by John Howard to be part of the formal National No campaign committee for the 1999 referendum.

At the time, I thought that my most important contribution at that convention was the speeches I gave.

I now realise it wasn’t.

I think my most lasting contribution was an attempt to move a motion.

The motion was ruled out of order – because it was beyond the scope of the Constitutional Convention.

And that motion was for a second referendum proposition – to formally recognise Aboriginal people in the Constitution.

In 1999, John Howard did ultimately put a question for constitutional recognition, but he did so without a formal process, without broader buy-in, and without the support of Indigenous people, and as such it failed.

Decades later, I feel incredible pride about being involved in the 1999 referendum campaign.

One of the joys of this campaign is working with such an eclectic group of Australians. I feel deeply privileged to be part of a group who want to make our country better.

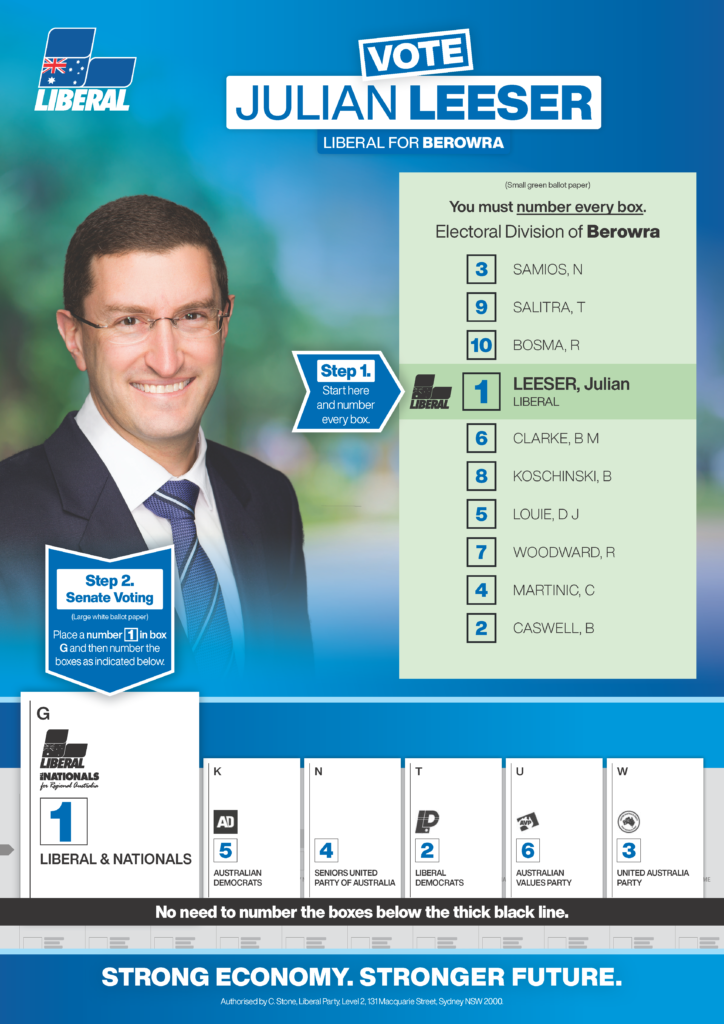

In my own electorate, we have trained over 200 volunteers. They come from every walk of life, and every political tribe.

Some of them have no political team.

Some of them, like me, are Liberals.

Some of them are quite proud of the fact they have never voted for me.

Someone this week showed me a tweet and it had an image of the Berowra for Yes t-shirt with the words “Finally something I agree with Julian Leeser on”.

I didn’t get too excited. The tweeter was my sister-in-law.

I am grateful for the members of the Liberal Party who are getting involved.

I met with some of the Liberal MPs from the NSW Parliament this week who are all voting who came to Canberra.

Along with their Leader, Mark Speakman SC, and former NSW Liberal premiers Dominic Perrottet, Barry O’Farrell and Mike Baird, they have all declared that they are voting Yes.

And there will be more that do so between now and referendum day.

They are being joined by many Liberal party members.

Only yesterday, the NSW State Director of the Liberal Party sent out an email – and pointed party members to sign up and get involved with the YES case or the NO case.

After all this is not about political parties or individual members of Parliament.

It is about the recognition through the Voice in our Constitution.

Our Shared Australian Story

I believe the Voice can be an instrument that brings Australia together.

Yes, there will be a decision, but I am increasingly optimistic that Australians are seeing this referendum as their next step in this shared national story.

I am a deeply conservative person. I am a constitutional conservative – and I am temperamentally conservative too.

Conservatives believe in the power of institutions to make countries stronger, stabler, and more enduring.

And as a conservative, I know that the strength of any country relies on the depth of bonds between all its people.

It’s one of the reasons I deeply oppose the work of the extremes in our national life – on what might be called the Corbynite far left and the Trumpian far right.

The strength of this country is found in the common sense, decency and good judgment of the vast middle of Australia.

The strength of the bonds between us as citizens matters profoundly.

For many years I have been reflecting on the place of Indigenous Australians in our national life.

We rightly now celebrate Indigenous Australians as part of our national story.

There was a time when we did not even acknowledge it.

It was called the ‘Great Australian Silence’.

A silence so profound that, when the first Parliament House in Canberra was opened in 1927, not one Aboriginal person was invited.

Two Indigenous men decided to attend at any rate.

Their names were Jimmy Clements and John Noble.

Clements was 80.

Reportedly they walked for 8 days to attend.

When they arrived, officials tried to turn them away.

Their presence was seen to be an embarrassment.

Fortunately, the crowd stopped the police from moving them on.

A moment where the decency and fair mindedness of Australians came to the fore.

It truly is wonderful that the national story we are telling our children has changed – that we celebrate what Noel Pearson calls the tripartite nature of the Australian story.

A story of three parts.

The first – Australia’s 65,000 years of Indigenous heritage, one of the oldest continuous cultures in the world.

The second – the British foundation – our institutions. Parliamentary democracy, representative and responsible government under the Crown, the rule of law, and the equality of all citizens.

And the third – our great multicultural character. A country where difference is celebrated.

In some ways, this referendum touches all three parts of that story.

It represents something deeper than story – it is grappling with who shares in the bounty of this land.

Across almost every measure, Australia is an extraordinarily wonderful place.

In terms of wealth, life expectancy, education, and opportunity we are more than lucky. We are blessed.

And yet, this bounty, this blessing, is not shared Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

Yes, as a country we have come far in terms of our outlook and attitudes towards Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. But we have made little progress in bridging the economic and social gaps between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians and other Australians.

Closing the Gap

What are those gaps?

Let me speak of some.

Aboriginal life expectancy is eight years less than that of other Australians.

The unemployment rate of Aboriginal Australians is nine times higher than that of their fellow Australians.

One in two Indigenous Australians live at or below the poverty line.

One in five Indigenous households are living in accommodation that does not meet an acceptable standard – either lacking a kitchen or sanitation.

The suicide rate for Indigenous Australians is two and a half times that of other Australians.

For too many Indigenous women and children, their lives are not safe.

In NSW, an Indigenous woman is 30 times more likely to present at a hospital with injuries from violence than other Australian women.

And an Indigenous boy in this country is more likely to go to jail than university.

The No case talks about risk – but the risk is not change, it is the same-old same-old.

But we can help change it.

How the Voice Will Close the Gap

I believe the Voice will help close the gap.

And it will do so by working with culture and community.

But first, let me explain what the Voice is and how it will work.

The Voice will be a committee of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians that will provide advice to the Federal government and the Federal Parliament.

The people on the Voice will be chosen by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. They will come from every state and territory.

The people on the national Voice will be drawn from local and regional bodies

Half will be men and half will be women – with spaces reserved for young people and people from remote areas.

They will have a fixed term.

The goal of the Voice is to help governments make better decisions – better decisions that come from listening to people.

Listening can bridge those gaps and improve outcomes.

All too often, we fail in Indigenous Affairs because governments think they know better than Indigenous communities.

And all too often, it fails because all too often government thinks that one size fits all.

Australia’s Indigenous communities are different.

The Kaurna people in Adelaide have different traditions, different histories and face different challenges, than the Larrakia people from Darwin or the Yirrganydji from Cairns.

When governments listen, when they consult, communities get better outcomes than when they don’t.

We all know from our own experiences that when governments consult, they make better decisions.

And it matters even more so when you are crossing cultures.

When the framers of the Constitution wrote the Constitution a century and a quarter ago – they were dealing with a practical issue and a cultural question.

The practical issue was to create the structures for one indissoluble Federal Commonwealth, but there was a cultural challenge: how to create one people.

That required trust – and give and take.

We see that in how we conduct referenda.

Not only a majority of people are required, but a majority of people in a majority of states.

Changing the Constitution meant not just winning the popular vote which could easily be dominated by the large population centres in Sydney and Melbourne, but winning the different parts of the country too.

And in this referendum, there are the words we are voting on – which I will go through shortly, but also on a deeper question “are we willing to hear the voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians?”

Are we willing to not see them as a people different and separate, but co-inheritors of this magnificent continent, its seas and isles. Voice and listening go hand in hand.

With a Voice and with listening, change is possible – because it embraces such beliefs as personal responsibility and personal respect.

When this happens expectations lift.

The 2021 Senior Australian of the year, Dr Miriam-Rose Ungunmerr Baumann speaks a great deal about ‘Dadirri’, which is deep listening.

Miriam-Rose speaks of Dadirri mostly in connection with the land. But the power of her idea lies in this – listening, deep listening, means connection.

So many of the social challenges we face are the result of disconnection.

Alcoholism, drugs, welfare dependency, mental illness, despondency, are all symptoms of disconnection.

Disconnection from land, disconnection from community, and disconnection with the other inhabitants of this land.

Listening results in connection, empowerment and respect.

There is a power in those ideas way beyond the law.

They can transform communities and remove what the songwriter Paul Kelly calls “this stone in our shoe”.

Let me give an example of what listening and deeply engaging can achieve.

Recently, I visited VACCHO in Melbourne who do great work with Indigenous health.

They have been grappling with the challenge of breast cancer in Indigenous communities.

In Australia, the incidence for breast cancer for Indigenous and non-Indigenous women is the same. But far more Indigenous women die from breast cancer.

The difference is the willingness to undertake screening.

So VACCHO spoke with Aboriginal women across the state about what made them hesitant about getting a screen.

They listened.

Indigenous women said they felt intimidated by hospitals.

In part it was because of the historic association of hospitals with trauma and death.

And also there was a lack of cultural connection, and there were concerns around modesty.

Three issues: 1. Historic, 2. Cultural connection and 3. Modesty.

So those concerns were answered with a project called The Beautiful Shawl Project.

Twelve communities designed shawls for the women to wear – with Aboriginal art, motifs and images.

And mobile clinics were taken to communities.

In those communities Aboriginal women turned out in force to get their tests. They felt welcome, confident and safe. That’s what listening does.

Likewise, recently I visited a school in East Arnhem Land.

It’s a partnership between Barker College, which is one of Sydney’s most prestigious schools, and the local community.

Barker has had to show the humility to listen – and they have.

Daily average school attendance is above 80 per cent – and at school, the children complain when there are school holidays.

This has occurred because they have identified ways of making the school an extension of the community rather than something separate from it.

Places for mums to catch up, warm breakfasts for the children, and teaching the local language alongside English.

There is the wonderful phrase from the Uluru Statement that captures this – it says:

“When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish. They will walk in two worlds and their culture will be a gift to their country.”

Voice, and listening, is about helping this country’s Indigenous children walk into two worlds. So they can thrive.

The Safe Change

Now this is a law school.

Whilst this lecture is not part of LAW 2501 taught by Dr Olijnyk, I want to speak about the confidence Australians can have in this provision.

This is a small change to the Constitution.

The opponents of the Voice say it’s a big change. It’s not.

In 1999, at the republic referendum, that proposal required 69 separate changes to the Constitution. This requires one additional section to be added to the Constitution. It is a change of about 100 words.

So, let’s go through what is being put to the Australian people.

On referendum day, Australians will be asked a question, it is

The question:”A Proposed Law: to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. Do you approve this proposed alteration?“

A straightforward question.

It is the question you will see on your ballot paper. And your job will be to write Yes if you support it or No if you oppose it.

And behind it a small amendment to the Constitution.

Let me read it to you:

Chapter IX Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples

129 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice

In recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia:

i. There shall be a body, to be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice;

ii. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice may make representations to the Parliament and the Executive Government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples;

iii. The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws with respect to matters relating to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice, including its composition, functions, powers and procedures.”

This provision provides recognition for Indigenous Australians, it establishes a permanent body to make representations, and the powers, functions, procedures, and composition of that body is a matter for the Parliament.

This change doesn’t cut across the grain of the Constitution, rather it flows with it.

Parliament is still supreme.

This is a legally sound change.

It is backed by three former High Court justices including a former chief justice.

It is backed by the Solicitor-General of the Commonwealth.

As well as various legal groups across Australia.

The Law Society of South Australia says about the provision that:

“The proposed Voice to Parliament is legally sound, constitutionally compatible, and aligned with the principles of representative and responsible government.”

Former Chief Justice of the High Court, the Hon Robert French AC, and your own Emeritus Professor Geoffrey Liddle AO wrote:

“The Voice is a big idea but not a complicated one. It is low risk for a high return… The Voice will provide a practical opportunity for First Peoples to give informed and coherent and reliable advice to the Parliament and the Government.”

The Solicitor General, Dr Stephen Donaghue KC, said:

“Insofar as the Voice serves the objective of overcoming barriers that have historically impeded effective participation by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in political discussions and decisions that affect them, it seeks to rectify a distortion in the existing system. For that reason, in addition to the other reasons stated above, in my opinion proposed s 129 is not just compatible with the system of representative and responsible government prescribed by the Constitution, but an enhancement of that system.

Former Chief Justice of New South Wales, The Hon Tom Bathurst AC KC is emphatic when it comes to the Voice and the sovereignty of Parliament:

“Any representations it makes can be accepted, rejected or indeed ignored by Parliament or the Executive. It has no law-making power; it is not an alternative Parliament; nor does it in any way limit the constitutional power of the Parliament or the powers conferred by Parliament on the Executive. Any argument to the contrary with respect is fanciful.”

And the respected Constitutional law Professor Anne Twomey AO reflects thoughtfully on what the words “may make representations” means in the provision:

“First, the word ‘may’ is permissive. There is no obligation on the Voice to make representations in relation to any particular matter. Second, the word ‘representations’ means formal statements expressing a particular point of view on behalf of a represented group.”.

She argues:

“The Voice would have political, not legal, influence. Political pressures would both give the Voice authority and operate as a constraint on its operation and effectiveness.”

That political and societal influence is needed because when it comes to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, we need to change direction as a country.

Conclusion

In the Federation debate, South Australia had an outsized influence on the Constitution.

Adelaide hosted one of the Conventions in the South Australian Parliament from 22 March to 23 April 1897.

South Australia was the leading defender of the rights of the smaller states.

But it was more than that – it was at the vanguard of political and social reform.

It was a South Australian, JH Howe, who was responsible giving the Commonwealth power over invalid and old age pensions.

It was a South Australian, PM Glynn, who moved that the preamble contain the words “humbly relying on the blessing of almighty God”, which helped recommend the Constitution to people of faith.

It was South Australians Charles Cameron Kingston and Sir John Downer who played key roles in the drafting of the Constitution, with Kingston developing his own draft of the Constitution prior to the 1891 convention and Downer serving on the drafting committee.

In fact, at Sir John Downer’s House (now part of St Mark’s College at this University), it is said that the Constitution was drafted on Sir John’s table by Sir John, Sir Edmund Barton and Richard O’Connor.

And most relevantly for our purposes today, it was Sir John Cockburn who moved that amendments to the Constitution be made by electors and not by conventions of the various states.

So we can thank that distinguished former South Australian Premier for the important exercise in democracy we will undertake on 14 October. It is an exercise which is all too rare in the democratic world, where the people not the parliaments have the power to amend their Constitution.

As small states men, the South Australian delegates were keen to defend the rights of the Senate.

It was a big thing for the colonial statesmen to give up power.

And the compatibility of federalism and responsible government was not entirely certain.

And so a century and a quarter ago, when considering the virtues of creating one country, the framers of the Constitution had a choice to listen to their fears or their hopes.

It was a big decision for states with smaller populations.

They had their fears about today might be called ‘the elites of Sydney and Melbourne’.

The citizens of the small states imagined and saw the opportunity that we now call Australia.

This nation in the 21st Century owes so much to the vision, hopes and courage of this country’s peoples from the 19th Century.

But they weren’t perfect. They didn’t get everything right – no generation does.

However, they got the big things right.

Federation and, of course, the legacy of the democratic reforms in this state – universal suffrage.

And so again in a new age there is a new constitutional question before us.

I believe this is a moment that Australians will thank us for.

We can make our country stronger – by listening, by walking together, and seeing the best in each other and not the worst.

We can heal our land. We can make it stronger. We can do this and more, by voting YES.