1 JUNE 2023

UNIVERSITY OF CANBERRA

Acknowledgements

It is only right that we begin with an acknowledgment of the Ngunnawal and Ngambri people and pay our respects to elders past, present and emerging.

Aunty Violet Sheridan, thank you for the welcome – and thank you for being a bridge, not only between cultures, but also being a bridge between the generations.

We can all learn from each other.

Our elders can give perspective, share learnings drawn from experience, and can see further because they have walked farther.

And the next generation carries with them their hopes, enthusiasms and ambition for the future.

If there is a time when we need wisdom and perspective as well as hope and enthusiasm it is surely today.

Professor Paddy Nixon, Vice-Chancellor, University of Canberra and Professor Maree Meredith, Pro Vice-Chancellor of Indigenous Leadership thank you for your kind invitation.

I know Professor Michelle Grattan wanted to be here.

It is with her work that I want to start.

In the millennium year of 2000, Michelle published a book called “Essays on Australian Reconciliation”. It was one of the quiet and understated ways Michelle has advanced the cause of reconciliation – not by drawing attention to her own views, but by creating spaces for others.

For me, she did that shortly after I was elected to Parliament, when Michelle arranged for me to have dinner with your Chancellor, Professor Tom Calma.

As Social justice Commissioner Tom had published a 2009 report Creating a sustainable National Representative Body for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples containing ideas which were a forerunner to the Voice.

Tom has been a wonderful sounding board for me at so many points along this road to recognition.

Michelle opened her book Reconciliation with a poem by Oodgeroo from the tribe Noonuccal.

It feels appropriate to also begin with some of Oodgeroo’s words given this is Reconciliation Week:

“We want hope, not radicalism,

Brotherhood, not ostracism

Black advance, not white ascendance;

Make us equals, not dependents,

We need help, not exploitation,

We want freedom, not frustration;

Not control, but self-reliance,

Independence, not compliance,

Not rebuff, but education,

Self respect, not resignation”

Hope. Brotherhood. Equality. Self-reliance. Freedom. Self Respect.

Timeless aspirations for no matter who you are, but aspirations all too often denied to Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Australians.

The journey to today

It feels appropriate that my first speech after the constitutional alteration passed the House of Representatives is to a university.

Because for me, that’s where my journey began.

About ten years ago, I was working at Australian Catholic University.

At that time, I had been working with a number of constitutional conservatives on a no campaign to stop the constitutional recognition of local government.

The Gillard Government had promised a referendum. Coincidentally, the minister responsible for advocating for change was Local Government Minister Anthony Albanese.

It was a campaign I was drawn to, because as a constitutional conservative, I was and am opposed to ideas that undermine the federation and which are a potential stalking horse for judicial activism – where judges get to decide policy decisions that are best left to the democratic process.

I am opposed to judicial activism because it is fundamentally undemocratic and undermines public confidence in our judiciary.

I believe contested political questions are best left to parliament. It is the Parliament that should reflect and advance the people’s will.

The plan for recognition of local government was so ill considered that eventually it was dropped by Labor.

It was at the end of our work trying to stop that referendum and we were having a celebratory meal, when I made a passing comment to the late Peter Reith about getting ready to oppose Tony Abbott’s plan for constitutional recognition.

Reith, the great proponent of referendum No Cases in 1988 and 1999, cautioned me with words to the effect “I’m not sure you can fight city hall on this one”.

It was a cryptic comment and it was enough to give me pause for thought.

And there began for me a journey, the start of a conversion on Indigenous Constitutional Recognition.

It was shortly after that my friend Damien Freeman and I, over a Passover meal, started working on the idea that could recognise the place of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians in our national life, without the need for a constitutional amendment.

The result was an idea of a non-constitutional Declaration of Recognition.

The idea of the Declaration was to create a defining statement that affirmed the unique and honoured place of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians in our national life. We could say so much more, if the Declaration was not hamstrung by the risks of judicial interpretation.

It was clear after we completed and released our work that it was not a complete answer.

I showed our work to my friend Christian Porter and his response was “I think this is a good idea but it needs something in the Constitution”. Christian was right.

The flowery words and symbolism-only approach taken for so long was neither attractive to Indigenous leaders or to conservative thinkers, so we started again.

Also at that time I started to engage with Noel Pearson and others.

Noel was also not happy with the state of the debate about constitutional recognition. He was seeking to understand the perspectives of constitutional conservatives and was looking for a way to encourage constitutional conservatives to vote yes.

Through our discussions, Noel came to understand that our constitution is a rule book, a practical charter of government, one that creates institutions.

I found myself being drawn more deeply into reflecting on the genuine aspirations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians to be recognised in their Constitution and for this to result in some sort of practical change in outcomes in their communities and in their lives

Led by Vice Chancellor Greg Craven the conversations continued. We listened, argued and brought others like Anne Twomey, Megan Davis and Marcia Langton into the conversations.

The result was something organic and consistent with our constitutional structures.

Unlike many other ideas in indigenous policy which are derivative of the experience of indigenous people in other countries, this was a wholly Australian idea built for Australian conditions.

It was called the Voice.

Not flowery language, but a practical structure that was about improved outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

It was an idea further enhanced when Tim Wilson and Warren Mundine put forward their idea for local and regional voices.Their idea enriched the entirety of our work.

Not only a Voice to the Parliament and Government, but one that could also speak through local and regional bodies to public servants, mayors and decision makers.

Then rightly, the idea was taken back to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

This process wound across Australia and culminated in the release of the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

It was a process of consultation, engagement and participation that truly embodied our Australian democratic ethos.

In that process, for the first time, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians were asked what they wanted from constitutional recognition.

They said they wanted a means to make a difference to life expectancy, to educational attainment, to job opportunities, to incarceration rates and to housing and safety too.

They wanted a Voice.

Remarkably, instead of rejecting the document that was silent about them for so long, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians embraced it.

As was so eloquently put at Uluru:

We seek constitutional reforms to empower our people and take a rightful place in our own country. When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish. They will walk in two worlds and their culture will be a gift to their country.

The path ahead

Yesterday, our country took another step on that path, with the House of Representatives passing the constitutional amendment.

It will go to the Senate later this month.

And then, after the alteration passes the senate, 18 million Australians will have to make a very important choice – at a referendum most likely in October.

Ahead of that is about a four month conversation.

It will be different from other national conversations.

It’s not a conversation about who governs us, or what political party or politician you might prefer.

It’s a conversation about a simple idea.

Shall we create an advisory body of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians that will help move the dial on the decisions that affect them?

That’s all.

The question we will all be voting on is 29 words:

“A Proposed Law: to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

Do you approve this proposed alteration?”

It’s a straight up and down yes or no proposition.

A proposition that will do three things in the constitution.

1. Recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Constitution

2. Give the Voice a permanent place in our Constitutional architecture, and

3. Reaffirm the supremacy of Parliament.

Tonight in this lecture, I want to talk about practicalities – to explain what the Voice will do, answering the main arguments against it, and how we can all play a role in creating a respectful debate.

The arguments for the Voice

Completing the Constitution

The first argument for the Voice is the reproach of history.

Our Constitution, the foundation document of modern Australia, the invisible pillar that holds our Federation together, makes no reference to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australia.

I love the Constitution – the framers of our Constitution did a remarkable job. They established a nation that would become one of the longest continuous democracies in the world.

As I said in my second reading speech, the underlying question our framers sought to answer was “how do we become one people?”

In so many ways they got it right.

The simplicity, sparseness and brevity of the Constitution has withstood the tests of time.

It is so right here in Canberra that we are surrounded by the names of those great men: Downer, Kingston, Barton, Isaacs, Reid and Griffith surround us in this capital.

But there was one glaring failure.

The framers, like all of us, were blinded by their own age.

They could not see and did not notice the Indigenous people of this land.

And our constitution became a conspirator in the great Australian Silence.

We can change that and complete our Constitution by recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians as the first peoples of our land.

The Voice completes our Constitution.

It is the capstone.

The system is broken

But we should not be trapped into thinking this referendum is about the past, it’s about the here and now, and the future.

Since Federation, there have been 44 referendum questions.

Most times, the no case offers a simple and compelling argument, it is “if it ain’t broke don’t fix it”. In the republic and on other occasions, we argued correctly, don’t change a system that works so well.

But when it comes to this referendum, we know that isn’t the case.

I have been to Alice Springs, Ceduna, Palm Island, Leonora, Laverton, Arnhem Land, and Aurukun, and I can affirm the system is broken.

Despite a shared national bipartisan effort, despite tens of billions of dollars, the gaps aren’t closing.

True, there has been incremental progress across many fronts – and I respect the work of so many across our country seeking to make a difference every day.

But even with all this effort, we are still failing.

The life expectancy of an Indigenous Australian is eight years below that of other Australians. Eight years.

Infant mortality is 1.8 times higher for Indigenous Australians than other Australians.

The unemployment rate for Indigenous Australians is estimated to be 30% – about 9 times higher than their fellow Australians.

One in two Indigenous Australians live in the most socially disadvantaged areas in Australia.

One in five Indigenous households are living in accommodation that does not meet an acceptable standard.

The suicide rate for Indigenous Australians is almost two and half times that of other Australians.

And currently, statistically, young Indigenous men are more likely to end up in jail, than attending a university like this one.

There are a thousand more statistics as damning as those.

And do you know the shocking thing, it is that most of us don’t see it or notice it.

The great risk in this referendum is not change, the great risk is the status quo.

I believe the Voice can change this.

I believe that local, regional and a national voice can make a difference in the issues that matter.

Listening, consulting and empowering

By listening to people and consulting people, by moving decisions closer to them, by empowering communities, and giving communities the self-respect that accompanies empowerment, we can make a difference.

By listening, consulting and empowering, we can get more Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children to school and keep them in school.

By listening, consulting and empowering, we can make a difference to services that tackle addictions and provide mental health support.

By listening, consulting and empowering, we can create stronger pathways to trades, skills, universities and eventually jobs.

And as importantly, by giving voice to communities, we can create the structures that can warn this country when communities are failing – when women and children aren’t being protected.

The Voice starts with a simple and straightforward public policy truth, that better decisions are made when you consult the people directly affected by them.

I look at our cities, and in communities like mine and yours here in Canberra, the public policies that work are a mix of top-down authority, and bottom-up community action.

Government and community in partnership. Listening, engaging, showing respect.

And that is what we are missing.

Michelle in her book wrote that progress was about making a material difference and that it also involves “intrinsically matters of the spirit”.

Respect, listening, engagement, and partnership.

It is about changing the way we do things when it comes to Indigenous affairs.

As Dr Chris Sarra, the respected Indigenous educator and director general has said “we have to stop doing things to Indigenous Australians and start doing things with them”.

As a taxpayer, I believe one of the benefits of the Voice will be getting a better bang for the buck.

The Voice won’t administer funds, it won’t allocate grants. But it should interrogate how funds are spent locally, it should question what’s working and what isn’t?

The Voice creates the frameworks and structures to make a difference at the local, regional and national level.

In a continent as vast as Australia, different solutions will be required for different communities.

The Voice will be a place for Ministers to road test policy to ensure it has maximum effectiveness when translated to community.

It’s about changing the status quo, because the status quo is the greatest risk.

Our national conversation

At the core of democracy is the willingness to have a conversation with our fellow citizens.

To convince each other of the path we must take.

I lament the moralisation of modern politics.

A moralisation that seeks to justify our own beliefs and views by asserting or inferring that those who disagree with us are somehow our moral inferiors.

A moralisation that assets that people voting yes are good and those voting no are bad – and vice versa.

I passionately disagree with that concept.

We are all Australians who love our country.

That’s why on polling day, when my wife Joanna and I help set up a polling booth at the end of our street – we are going to bring the drinks, sandwiches and biscuits for both the yes and the no case workers.

We might even make the biscuits using the shape of the Australian continent – and I promise not to forget Tasmania.

You see, I believe the best way to persuade people is to start by respecting them.

That’s not rocket science, but we’ve all seemed to have forgotten that in modern politics.

So let me respectfully answer the three key arguments of the no case.

Answering the No Arguments

The first argument is that we don’t need a voice because we have 11 Indigenous members of parliament.

At one level, that argument speaks of some national progress, and it is wonderful we have so many members and senators from across the political spectrum: Liberals and Nationals, Labor, the Greens and Independents.

But all of them are elected to represent communities of people – Indigenous and non-Indigenous, immigrants, young and old, and of all backgrounds.

And most are there to represent their party and the values and ideals of their party.

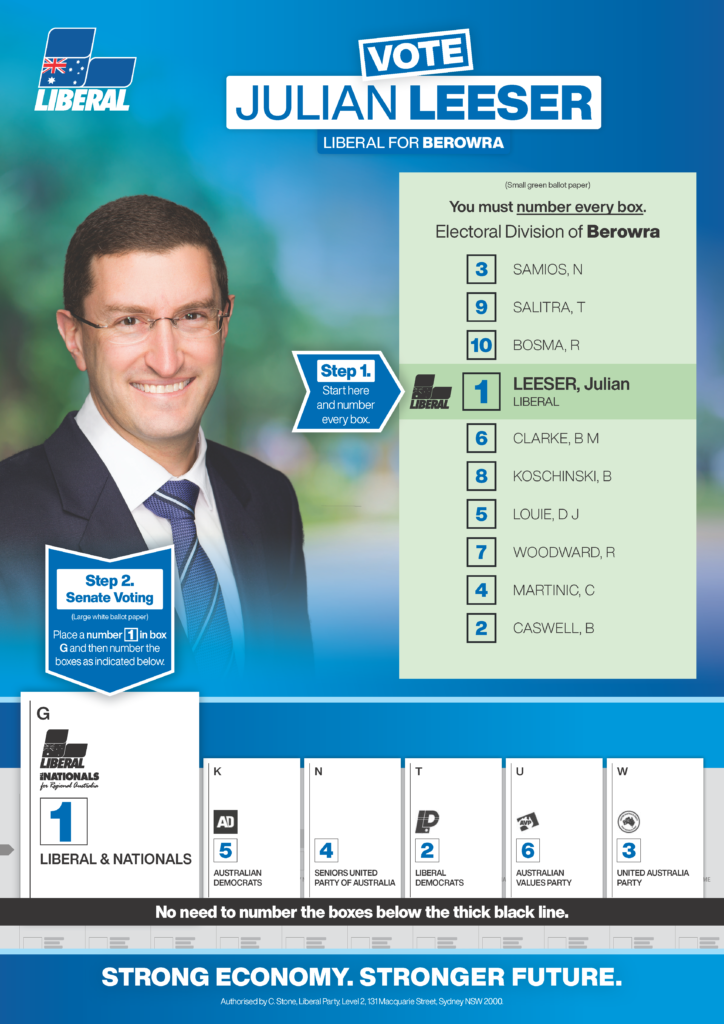

I am a Jewish member of parliament. I am currently the only Jewish Liberal Member of Parliament. But whilst I am Jewish, I am not in Parliament as the representative of Australian Jews, I am in the parliament representing the people of Berowra. I am the representative of the people of Berowra and they have elected me as their Liberal representative.

No one in either chamber of parliament is there as a representative of a race, ethnic group or religion.

So it’s a misnomer to suggest that Indigenous Recognition is achieved through the democratic participation of Indigenous Australians in the parliament. It’s not.

The second argument is the Voice will create a new level of bureaucracy.

The no case argues that the Voice is a greedy power grab so that Indigenous people can make decisions about paper clips and parking fines to submarines.

My answer is: really?

Painting our submarines in indigenous colours is not a priority, nor is determining what indigenous ingredients are served to the submariners.

We all know what the priorities are: infant mortality, pre-school attendance, school attendance, access to housing, family safety, tickling addictions, high school completion, incarceration and recidivism, the suicide rate and life expectancy.

The constitutional amendment allows the Voice to make representations.

It doesn’t require the parliament, or any agency to follow slavishly the ideas put forward. It doesn’t in any way subvert the Parliament.

The Voice isn’t delivering tablets of stone.

The Voice’s considerations, observations and advice will be weighed by the Parliament, the government, and various states and local authorities.

Just like governments weigh information and advice from the security services and police, from DFAT and the agriculture department, and from the Chief Scientist and Chief Medical Officer.

The Voice can make a difference by highlighting what is and isn’t working, particularly at the local and regional level.

There is no new fourth layer of government, or for that matter third chamber of parliament or new house of lords.

But there will be, I hope, more voices, more wisdom and more experiences, adding to the decisions made by government and the public service.

In a democracy, that is always a good thing.

The third argument is that the Voice will divide Australians by inserting race into the Constitution.

Race is already in our Constitution and it always has been.

Section 51(xxvi) of the Constitution, gives parliament the power to make laws for “the people of any race for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws”.

So there is already a race power.

In 1967, Australians extended the race power to make laws about Aboriginal people, but I don’t believe the Voice is about race. It is not about the elevation of one colour over another, but it is about the First Peoples of Australia.

It is about Australians who have a deep connection to this land – and indeed, a deep disconnection to the opportunities their fellow citizens share.

Some have said why not a voice for the Indians, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, German and Kurds?

There are two reasons. The first is that the position of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is unique given their status as the First Peoples of Australia.

The second reason is that for sixty years, the race power has been used to make laws about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. They are the only people about whom we make laws on the basis of their race.

Billy Wentworth, the Commonwealth’s first minister responsible for Aboriginal Affairs and a remarkable Liberal, often remarked that when Aboriginal language or culture or opportunity was lost, the whole country suffered, because it was our shared loss.

There’s a truth in that.

And there is also a truth that the reconnection of Aboriginal people to the full opportunity of Australia is something we will all share in.

In my conversations with immigrant communities, they know through their own experiences that Australia is the most successful multicultural nation on Earth.

It’s part of our modern Australian ethos that we show respect to all peoples – and the Voice is consistent with demonstrating a deep respect to our First People, dispossessed not only from the land but from the outcomes achieved compared to others.

The implied argument is that the Voice is ‘racist’, but that argument fails to recognise that racism and prejudice is always built on disrespect.

Racism is never the result of respect, only disrespect.

In this proposal, there is no disrespect to any other Australian – be they the descendants of First Fleeters or those who took their citizenship pledge last week.

All Australians remain equal – and the Voice is about giving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders a better shot at the equality achieved by all other citizens.

Conclusion

There is a lovely coincidence occurring this week.

This weekend marks 125 years since the first referendum questions were posed seeking the people’s support to become a federation.

It was an act of faith and trust.

But it wasn’t a misplaced faith.

A decade of work had been done to make sure it was right.

Not everyone got what they wanted, and I certainly understand that in this debate.

The work has been done.

A decade of debate. Conversations to and from Uluru.

Multiple reports and debates.

We are approaching the time to decide.

To all I ask, engage with this debate. Listen to each other.

Listen to the doubts of those who fear change as well as the dashed hopes of those who know the failings of the status quo.

This referendum is a choice we will all have to make.

I am confident that the referendum is an opportunity for real change and progress for Australians.

The Voice will lay the foundation for a positive change in the opportunities before Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Australians.

We should embrace the moment, confident that through listening and empowerment we can all make a serious difference to the lives of our Indigenous brothers and sisters.

Thank you for inviting me to be your first speaker in this series of lectures.